Difference between revisions of "Restoration planning"

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

# Developing a monitoring and evaluation programme | # Developing a monitoring and evaluation programme | ||

# Participation and fully consultation of stakeholders | # Participation and fully consultation of stakeholders | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == ''Endpoints'' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is imperative that endpoints accompany benchmarking in the planning process to guarantee the prospect of measuring success because endpoints are feasible targets for river rehabilitation. It is important to note that endpoints are different to benchmarks, this is because other demands on the river systems also have to be met and references can only function as a source of inspiration on which the development towards the endpoints is based (Buijse et al. 2005). Given that benchmark standards cannot always be achieved, especially on urban rivers, endpoints will therefore assist in moving restoration effort forward through application of the SMART approach, to decide what is achievable and what is feasible. There is a need to distinguish endpoints for: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Individual measures | ||

| + | * Combination of measures | ||

| + | * Catchment water bodies | ||

| + | * River basin districts | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == '''Planning protocol for river restoration''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | With an increasing emphasis on river restoration comes a need for innovative tools and guidance to move decisions based largely on subjective judgments to those supported by scientific evidence (Boon & Raven 2012). The restoration planning protocol developed uses project management techniques to solve problems and produce a strategy for the execution of appropriate projects to meet specific environmental and social objectives (Figure 2). The procedure is process driven in its development and makes use of various project planning tools (e.g. PDCA, DPSIR, conflict resolution, environmental impact assessment and logical framework, SMART and participation ladders) to: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Diagnose problems and produce a strategy for their remediation; | ||

| + | * Provide knowledge of the technical policy and background to conflicts of multiple use of resources; | ||

| + | * Develop a plan based on benchmarking and endpoints for setting specific and measurable targets with objectives as defined by the institutional, regional, national policy; | ||

| + | * Ultimately develop action plan with actions and targets, whilst recognising the need for an integrated approach to management of resources to minimise conflicts and optimise use. | ||

Revision as of 13:49, 12 May 2014

Contents

Constraints in identifying river rehabilitation project success

Little is known about the effectiveness of river restoration efforts despite the rapid increase in river restoration projects. Restoration outcomes are often not fully evaluated in terms of success or reasons for success or failure and this is, in part, due to weaknesses in the design and implementation stages of project planning for rehabilitation schemes. The review of concepts to measure the success of river restoration found that despite large economic investments in what has been called the “restoration economy”, many practitioners do not follow a systematic approach for planning restoration projects. As a result, many restoration efforts fail or fall short of their objectives, if objectives have been explicitly formulated. Some of the most common problems or reasons for failure include:

- Not addressing the root cause of habitat degradation

- Poor or improper project design, skipping key design steps

- Expectations not clearly defined with measurable objectives, therefore project success is difficult to evaluate through monitoring (Bernhardt et al. 2007)

- Not establishing reference condition benchmarks and success evaluation endpoints against which to measure success

- Failure to get adequate support from public and private organizations

- No or an inconsistent approach for sequencing or prioritizing projects (Roni et al. 2013)

- Inappropriate use of common restoration techniques because of lack of pre-planning (one size fits all) (Montgomery & Buffingtion 1997)

- Inadequate monitoring or appraisal of restoration projects to determine project effectiveness (Roni & Beechie 2013)

- Improper evaluation of project outcomes (real cost benefit analysis)

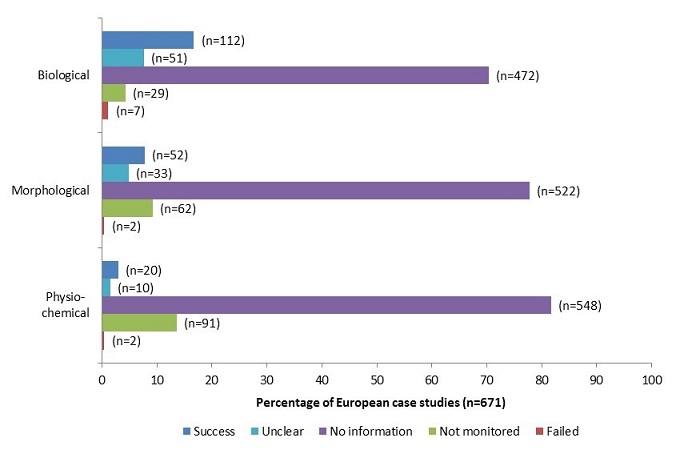

Figure 1. Success rate of 671 European case studies recorded from the REFORM WP1 database.

Figure 1. Success rate of 671 European case studies recorded from the REFORM WP1 database.

Benchmarking, Endpoints and project success

Overall, evaluating how successful restoration measures have been, as well as determining reasons for success or failure are essential if restoration measures are to meet obligations under the WFD. Setting benchmarks and end points that are linked to clearly defined project goals is considered the most appropriate approach to help measure of success (Buijse et al. 2005).

Benchmarking

Benchmarking as a tool should be feasible, practical and measureable to help guide future decision support tools. One of the first steps is to establish benchmark conditions against which to target restoration measures. Benchmarking uses representative sites otherwise known as ‘reference sites’ on a river that have the required ecological status and are relatively undisturbed; this is then used as a target for restoring other degraded sections of river within the same river or catchment. This requires:

- Assessment of catchment status and identifying restoration needs before selecting appropriate restoration actions to address those needs

- Identifying a prioritization strategy and prioritizing actions

- Developing a monitoring and evaluation programme

- Participation and fully consultation of stakeholders

Endpoints

It is imperative that endpoints accompany benchmarking in the planning process to guarantee the prospect of measuring success because endpoints are feasible targets for river rehabilitation. It is important to note that endpoints are different to benchmarks, this is because other demands on the river systems also have to be met and references can only function as a source of inspiration on which the development towards the endpoints is based (Buijse et al. 2005). Given that benchmark standards cannot always be achieved, especially on urban rivers, endpoints will therefore assist in moving restoration effort forward through application of the SMART approach, to decide what is achievable and what is feasible. There is a need to distinguish endpoints for:

- Individual measures

- Combination of measures

- Catchment water bodies

- River basin districts

Planning protocol for river restoration

With an increasing emphasis on river restoration comes a need for innovative tools and guidance to move decisions based largely on subjective judgments to those supported by scientific evidence (Boon & Raven 2012). The restoration planning protocol developed uses project management techniques to solve problems and produce a strategy for the execution of appropriate projects to meet specific environmental and social objectives (Figure 2). The procedure is process driven in its development and makes use of various project planning tools (e.g. PDCA, DPSIR, conflict resolution, environmental impact assessment and logical framework, SMART and participation ladders) to:

- Diagnose problems and produce a strategy for their remediation;

- Provide knowledge of the technical policy and background to conflicts of multiple use of resources;

- Develop a plan based on benchmarking and endpoints for setting specific and measurable targets with objectives as defined by the institutional, regional, national policy;

- Ultimately develop action plan with actions and targets, whilst recognising the need for an integrated approach to management of resources to minimise conflicts and optimise use.